Systemic Amyloidosis (SA) results from tissue deposition of insoluble protein fibrils leading to organ dysfunction. Considering the scarcity of data from Latin America, a retrospective study was conducted by reviewing medical records of patients with biopsy proven SA diagnosed from 2009 to 2018 at a public tertiary center to assess clinical, laboratory and therapeutic features.

Confirmed SA subtype was established if causative protein was identified on tissue biopsies by immunohistochemistry (IHC), indirect immunofluorescence (IIF), mass spectrometry (MS) or in the presence of pathogenic gene mutation related to SA. Probable cases were classified as light chain SA (AL) if evidence of monoclonal gammopathy (MG), transthyretin SA (ATTR) if moderate/strong cardiac uptake in 99mTc-pyrophosphate scintigraphy (99mTc-PYP), classical neurological symptoms with familial history or previous liver transplant from a donor with hereditary ATTR (hATTR), and secondary SA (AA) in the context of underlying chronic inflammatory disease. Inconclusive cases had ≥2 concomitant features suggestive of different subtypes.

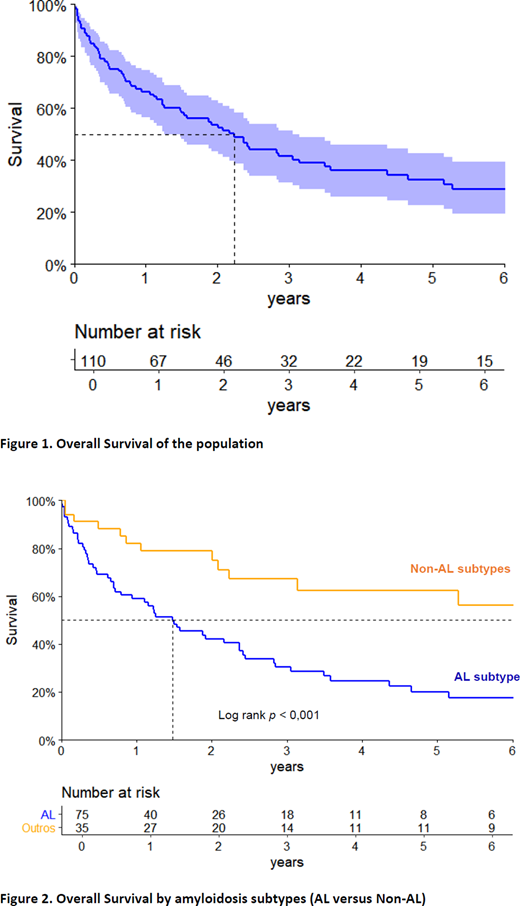

Primary endpoint was overall survival (OS).

From 198 cases revised, 110 met the eligibility criteria. Median age was 60 years, 56% were male.

Before diagnosis 53% were seen by ≥3 physicians: 65% general practitioners, 45% nephrologists, 42% cardiologists. Median time from onset of symptoms to diagnosis was 11.3 months. In 79% of patients ECOG was ≤2.

Clinical presentations were: 54% renal disorders, 43% heart disease, 36% consumptive syndrome, 26% gastrointestinal symptoms, 25% neuropathy, 19% fatigue, 12% skin lesions, 9% hepatic disorders.

The mean number of biopsies performed per patient was 2.3 and 60% had a method to subtype amyloid on biopsy: 67% IIF, 36% IHC and MS in 1 case.

Mean number of affected organs was 2.6 (19% 1 organ, 38% 2 and 43% ≥ 3). Main organs were: 75% heart, 55% kidney, 43% soft tissue, 37% peripheral nervous system. Dialysis patients were 12%.

Positive familial history was seen in 7% and 17% were tested for genetic mutations: 63% for transthyretin, 21% fibrinogen, 5% lysozyme, 16% MEFV gene.

MG screening was assessed in 97% of patients, amyloid protein A in 4 and 99m Tc-PYP performed in 11.

SA subtypes were confirmed in 32% of patients, probable in 59% and inconclusive in 9%. Frequency of subtypes were 68% AL, 12% ATTR, 6% AA, 4% fibrinogen amyloidosis (AFib), 1% lysozyme amyloidosis (ALys).

Most of AL were λ (75%) and 34% had coexisting multiple myeloma. Standard Mayo Clinic Staging (MCS) was evaluated in 56% (59% stage III, 31% II, 10% I). Stage III were assessed by European staging (32% IIIa, 48% IIIb, 20% IIIc). Revised MCS was available in 21% (25% each I to IV). Renal staging showed 81% stages I/II, 19% stage III.

Among ATTR patients 1 was wild type and 69% had mutation in TTR gene: 44% V30M, 33% V122I, 11% G89L. In 11% genetic data were not assessed. Mutated ATTR was presumed in 2 domino liver transplant recipients from hATTR donors.

Inflammatory diseases in AA were: 43% Familial Mediterranean Fever (FMF), rheumatoid arthritis, vasculitis, immunoglobulin G4-related disease, combined polymyositis/primary biliary cholangitis (14% each).

Treatments in AL were: 81% chemotherapy (CT) (54% melphalan, 18% thalidomide, 10% bortezomib), 12% stem cell transplant, 12% supportive measures (SM), 4% doxycycline, 1 kidney transplantation. Responses were available in 40 cases: 30% PR, 13% VGPR, 18% CR, 25% no response, 15% progression.

ATTR was treated with: 31% liver transplantation, 54% SM, 8% tafamidis, 8% doxycycline.

AA related to FMF treatments were anti-IL1 and colchicine and other AA received immunosuppressive therapy for underlying diseases.

ALys was treated with SM. CT was given to 1 AFib patient before proper diagnosis, the others received SM.

Inconclusive cases were managed 90% with SM, 1 received empirical CT.

Median follow-up time of survivors was 66.3 months. At 5 years, estimated OS was 33%. Median OS in AL and non-AL were 18 and 74.4 months respectively (p < 0.001).

In conclusion, the broad clinical spectrum of SA and the complex diagnostic approach lead to late diagnoses in advanced stages. Medical awareness of the disease, early suspicion, establishment of reference centers, better diagnostic tools, multidisciplinary team, a SA registry and access to disease-modifying drugs may result in early diagnosis and prompt intervention, improving outcomes in Brazil and Latin America.

No relevant conflicts of interest to declare.

Author notes

Asterisk with author names denotes non-ASH members.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal